🔮🧠 The Neuro-Coder (Part 2): The Cognitive Architecture of 'Vibe Coding'

This is Part 2 of The Neuro-Coder. In Part 1, we looked at the dopamine loops that hook us. Now, we look at the biases that keep us trapped.

We need to talk about “Vibe Coding.”

The term has taken off as a cool, futuristic way to describe coding with AI (I have opinions and have been known to get on a soapbox about this). It implies a state of pure flow, where you, the orchestrator, just “vibe” with the machine, directing high-level intent while the AI handles the grunt work.

It sounds magical. But if you’ve ever spent 45 minutes trying to get your AI assistant to fix a CSS centering issue that you could have fixed in 30 seconds with flexbox, you know the dark side of the vibe.

That state isn’t “flow.” It’s Cognitive Entrapment.

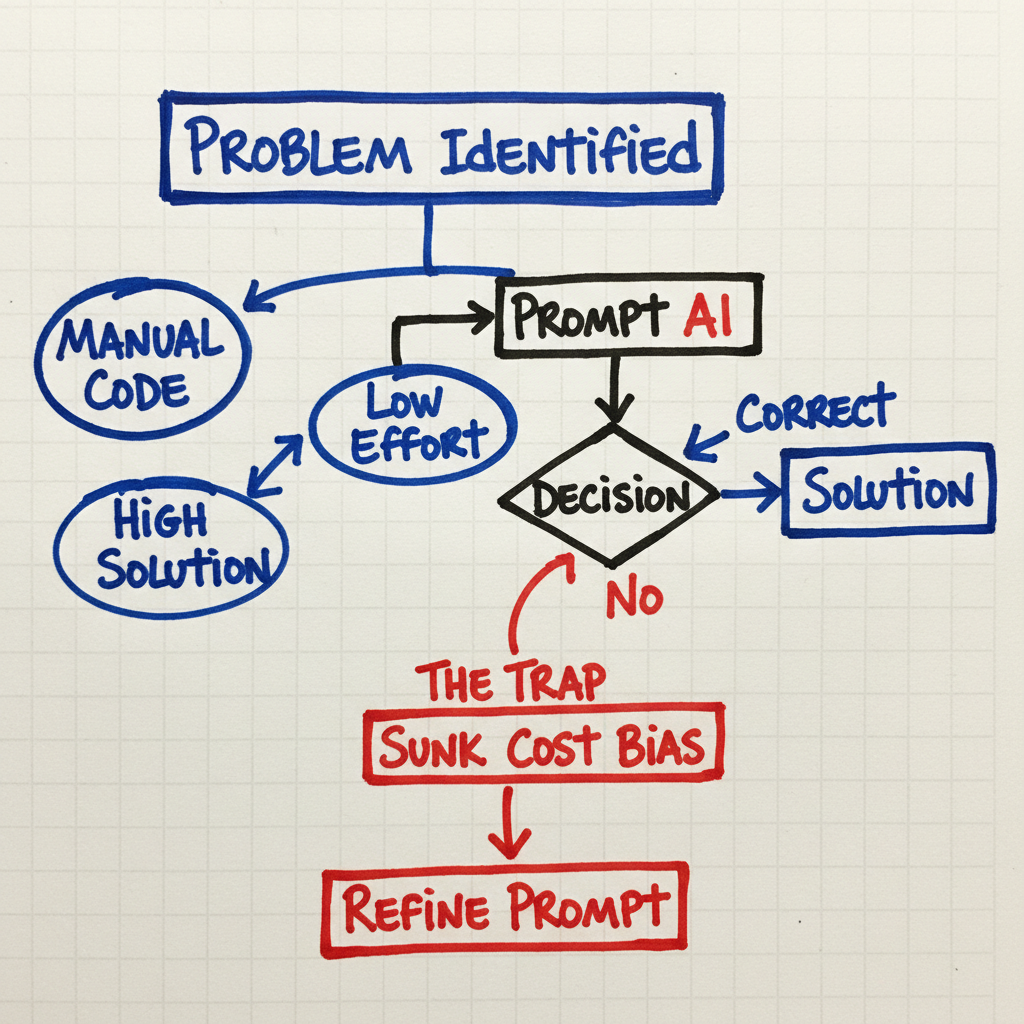

Why do we do it? Why do we stare at a chat window, tweaking a prompt for the tenth time, when the solution is right there at our fingertips?

It’s not because we’re lazy. It’s because our brains are being hacked by three specific cognitive biases.

1. The Sunk Cost Fallacy & The “Context Switch” Tax

We all know the Sunk Cost Fallacy. It’s why you finish a terrible book just because you’re 100 pages in.

In “Prompt Engineering,” this fallacy is deadly.

You write a prompt. The AI generates code that is almost right but hallucinating a library.

- Rational Brain: “This isn’t working. I should check the docs and write it.”

- Bias Brain: “I’ve already invested 5 minutes in this prompt. If I stop now, that time was wasted. I just need to tell it to use the other library.”

So you re-prompt. It fixes the library but breaks the logic. You re-prompt again.

Suddenly, you’re 30 minutes deep. You are “Chasing the Loss.”

But it’s not just stubbornness. It’s also Context Switching Cost. To stop prompting and start coding, you have to load the entire syntax and variable state into your Working Memory. While prompting, that state is held externally (in the chat). Your brain is rationally trying to avoid the metabolic cost of “loading” the code. But this laziness traps you in a loop of negative productivity.

The Counter-Argument: Some might argue this is an “Epistemic Action”—using the AI to simulate solutions to help us think. But this only works if you analyze the result. If you are just skimming and re-prompting (driven by Completion Bias), you aren’t learning; you’re just consuming.

2. The “Reverse” IKEA Effect (Prompt Ownership)

The IKEA Effect is a well-known psychological phenomenon where we overvalue things we build ourselves. That wobbly bookshelf you assembled? You love it more than the sturdy one you bought pre-assembled.

With AI, we see a fascinating mutation: the Reverse IKEA Effect.

We don’t write the code. The AI does. So, logically, we shouldn’t feel attached to it. But we do write the Prompt.

We transfer our sense of ownership from the Code to the Prompt. This is especially strong with “Mega-Prompts.” If you spent 15 minutes crafting a detailed specification, you will defend the output far more vigorously than if you just typed “fix bug.”

The Danger: This creates Prompt Ownership Bias. But it also creates Diffusion of Responsibility. Because “the AI wrote it,” we feel less responsible for the bugs. We assume the code is “standard” or “correct” because it came from a “superior” intelligence (Automation Bias). This double-whammy—defending the prompt while disowning the code—is a recipe for bugs.

3. Completion Bias (The Productivity Placebo)

Humans love closure. Our brains release dopamine when we finish a task.

AI tools are masters of the Visual Placebo. You hit Enter, and boom—screen full of code.

- Visual Cortex: “Task Complete! Look at all those pixels!”

- Logical Brain: “Wait, I haven’t read it yet.”

But the dopamine hit has already happened. The Completion Bias kicks in. We feel a “Sugar High” of productivity. We see a green diff, and we assume “Progress.”

This leads to the Verification Gap. Because we feel like we’re done, the act of verifying the code feels like a buzzkill. It feels like “extra work” rather than “the actual work.” So we skim. We “LGTM” our own AI code. We accumulate technical debt because the visual sensation of speed is more addictive than the reality of quality.

☕ The Takeaway: The “Vibe Check” Checklist

Awareness is the only cure. The next time you feel that frustration rising, or that defensive twinge in a code review, run this checklist:

- The Sunk Cost Check: “If I hadn’t written this prompt, would I start writing this code manually right now?” (If yes, stop prompting. Start typing.)

- The Ownership Check: “Am I defending this code because it’s good, or because I feel clever for generating it?”

- The Reality Check: “Does this code work, or does it just look like it works?”

In Part 3, we’re going to look at the hard data that proves this isn’t just a feeling. We’ll dive into the METR Study and the massive gap between how fast we feel and how fast we are.

🔬 The Hypothesis & The Request

This post proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis: “Vibe Coding” is not a sustainable workflow; it is a manifestation of cognitive biases—specifically the Sunk Cost Fallacy and the Reverse IKEA Effect—that irrationally entrench AI usage even when it is inefficient.

Research Question I’d Love to See Answered:

We need rigorous Time-Motion studies. Does the time spent “refining prompts” actually beat the time spent “typing code” for complex tasks? Or is the “Vibe” just a mechanism to mask our own inefficiency?

📚 Further Reading

- The Metacognitive Gap: “It’s Weird That it Knows What I Want”: Usability and Interactions with Copilot for Novice Programmers (Prather et al., ACM TOCHI 2023). A landmark study showing that novices often believe they understand AI-generated code, but fail when asked to modify it manually—a phenomenon the authors describe as an “illusion of competence.”

- The IKEA Effect: The IKEA effect in human-AI collaboration (Marketing Science). Research on overvaluing co-created output.

- Commentary: Vibe Coding Is Creating Braindead Coders (Namanyay Goel) & Generative AI runs on gambling addiction (Pivot to AI). Thought-provoking essays on the behavioral loop.